From the magazine that brought you “black women are ugly because they’re fat, stupid and manly” comes a shower of fresh herpetic pus.

The title alone is thoroughly awful: “Attention, Ladies: Semen Is An Antidepressant“. It is steeped in various societal expectations regarding women and sex: women don’t really like semen, and it is up to the men (and male columnist) to persuade them otherwise.

The science is equally shaky; the column itself links three thoroughly unrelated concepts.

It begins with a discussion of the McClintock Effect, the phenomenon where women’s menstural cycles sync when they live or work together, which is apparently due to pheromones (which may not even exist in humans) (and the evidence for the McClintock effect is fairly poor in and of itself) (basically it’s bollocks). According to the article, the phenomenon does not occur in lesbians, and it is posited that the only difference between heterosexual women and lesbians is exposure to semen.

This assertion is complete rubbish for a number of reasons, and I promise I am not oversimplifying the text of the article. It actually says this:

But at the State University of New York, two evolutionary psychologists were puzzled to discover that lesbians show no McClintock effect. Why not? Gordon Gallup and Rebecca Burch realized that the only real difference between lesbians and heterosexual women is that the latter are exposed to semen.

The absence of a scientifically-dubious effect in lesbians is due tolesbians being unexposed to semen. There is no mention of the existence of bisexual/queer women, and absolutely no critical thinking regarding whether there are other lifestyle differences between lesbians and heterosexual women.

Furthermore, they put this ridiculous assertion into the mouths of the cited evolutionary psychologists who published the semen-is-an-antidepressant paper. They wrote nothing of the sort in the original paper (sadly paywalled). Quite what lesbians and their lack of a dubious effect has to do with semen as an antidepressant is unclear, but it speaks volumes about the quality of science reporting in Psychology Today.

I read the whole paper. I had to find it myself, as Psychology Today cited an article in a popular science magazine, outright admitting to churnalism. It is entitled “DOES SEMEN HAVE ANTIDEPRESSANT PROPERTIES?”. Psychology Today summarised it as this:

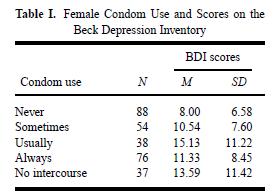

Given vaginal absorptiveness and all the mood-elevating compounds in found in semen, Gallup, Burch, and SUNY colleague Steven Platek wondered if semen exposure might be associated with better mood and less depression. They surveyed 293 college women at SUNY Albany about intercourse with and without condoms, and then gave the women the Beck Depression Inventory, a standard test of mood. Compared with women who “always” or “usually” used condoms, those who “never” did, whose vaginas were exposed to semen, showed significantly better mood–fewer depressive symptoms, and less bouts of depression. In addition, compared to women who had no intercourse at all, the semen-exposed women showed more elevated mood and less depression.

Meanwhile, risky sex is usually associated with negative self-esteem and depressed mood. Among college women, risky sex includes intercourse without condoms, so we would expect sex sans condoms to be associated with more depressive symptoms, and more serious depression including suicide attempts. However, in the Gallup-Burch-Platek study, among women who “always” or “usually” used condoms, about 20 percent reported suicidal thoughts, but among those who used condoms only “sometimes,” the figure was much lower, 7 percent, and among women who “never” used condoms, only 5 percent reported suicidal thoughts. (This study controlled for relationship duration, amount of sex, use of the Pill, and days since last sexual encounter.) So it appears quite possible that the antidepressants in semen might have a real mood-elevating effect.

The first paragraph is largely correct: 293 women were surveyed, using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which is a self-report questionnaire designed for screening for depression. The BDI is limited in its utility as it is a self-report measure, and it also contains a mixture of physical and emotional symptoms.In samples of college students, the BDI may not necessarily measure depression, but rather, general psychopathology, meaning that in this study, the authors may not have been measuring depression, and therefore it is not possible to conclude that semen has antidepressant qualities as depression has not been measured.

The second paragraph is rather misleading. The authors did not control for any of the variables that the article said it controlled for. The results section of the original paper is what can only be described as a clusterfuck of various correlations, none of which actually include controlling for anything. The women differed on many of the variables, for example, on frequency of intercourse (the women who never used condoms had the most sex). This was not statistically controlled for: everything was simply chucked into the same regression model. The model was not significant and explained a trivial amount of the variance in depressive symptoms. Although the coefficient for condom use was statistically significant, the coefficient itself was small, and likely trivial.

Important variables were also not measured: for example, the authors failed to measure the quality of the relationships the women were having, something which may be highly relevant to their mood.Furthermore, the authors had adequate data to identify a “dose-response” relationship–in keeping with their hypothesis that semen is an antidepressant, there should be a relationship where women who were had greater exposure to semen reported lower depressive symptoms and vice versa. This could easily be analysed from data, combining condom use frequency and frequency of intercourse. It is not. I wonder if they ran the analysis and nothing emerged?

The authors also fail to comment on a very noticeable pattern in their results:

The women who reported always using condoms had markedly lower BDI scores than those who used condoms “usually”. This pattern was also present in the data regarding suicide attempts. It runs counter to the authors’ hypothesis: the women who always used condoms, by the authors’ use of condom use as a proxy for exposure to semen, were less depressed than those who would sometimes be exposed to semen.

The suicide attempts data is bafflingly high. 29% of the women in the “usually” use condoms group had reported previous suicide attempts. The population average is about a tenth of this. It is probably that the data were gathered poorly. Given all of the other effect sizes, it is highly unlikely that exposure to semen is related in any way to a ridiculously high rate of suicide attempts.

On the whole, then, the study is shaky at best, though the phrase I would use would be “HOW THE FUCK DOES SHIT LIKE THIS MANAGE TO GET ITSELF PUBLISHED?” followed by throwing my (as yet entirely unpublished) PhD at a wall.

The Psychology Today article then flies off on another tangent, discussing human concealed ovulation, a topic of obsession for evolutionary psychologists. According to speculation, semen can force ovulation in a woman. It is such unsupported bollocks that to destroy this would be like punching a kitten in the face.

The Psychology Today article ends on an important caveat:

Now, I’m not advocating that reproductive-age people shun condoms to elevate women’s mood at the risk of unplanned pregnancy. But this effect might come in handy for women over age 50, who are experiencing menopausal blues.

There are so many things wrong with this paragraph that it is hard to know where to begin. It is commendable that the columnist thinks that unprotected fucking is not the way to cure depression. He is, however, completely oblivious to the fact that the risks of unprotected fucking go far beyond “unplanned pregnancy”. If he is, as I suspect, an evolutionary psychologist, it is understandable why he thinks that: the evolutionary psychologists tend to construct sex as something for nothing more than reproduction. He is also utterly wrong about how this effect may be useful for menopausal women. Even if we pretend that the semen-antidepressant study was done really well, the findings still only apply to young women.

In sum, then, spunk will not cheer you up or stop you killing yourself. Don’t avoid condoms unless it is safe for you to do so. The science is thoroughly awful.

If sex cheers you up, have sex, with the level of protection of your choosing. It is unlikely that it will be a magic panacea, but a good fucking is tremendous fun.

__

Big thanks to Tom, Alice and Fabi in the PhD room for reading through this drivel with me and having brilliant scientific brains