Earlier this week, several news outlets breathlessly reported on a new study which had found that (gasp) two thirds of 16-19 year olds in Europe are engaging in risky or criminal activity on the internet. One of the authors, doing the press rounds, explicitly spoke out in favour of the upcoming Online Safety Bill, as a way of keeping these naughty, naughty kiddos safe from themselves.

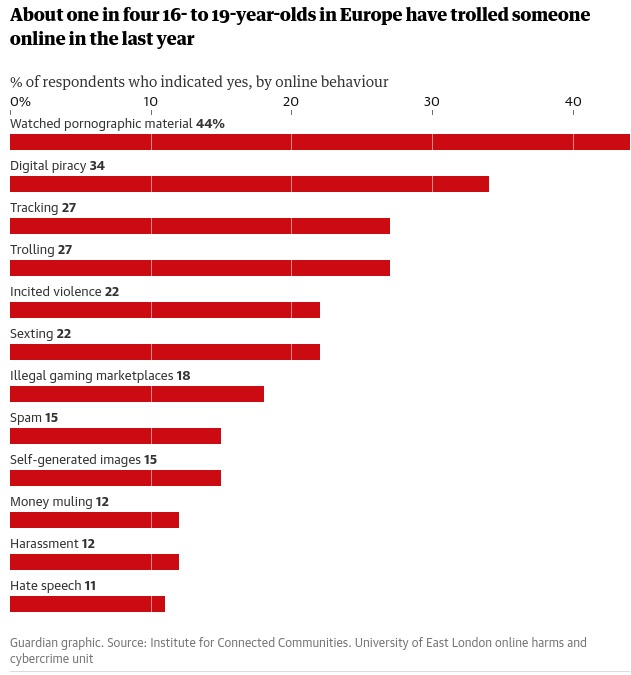

This, of course, triggered my bullshit radar, and this graph in the Guardian in particular caused a forehead sprain from raising my eyebrows too hard.

Are you seeing what I’m seeing? Sticking watching porn or a poor-quality and free stream of a show right there alongside things like money laundering and hate speech? Let’s bear in mind that a sizeable portion of them are literally legally adults. You may also be wondering what some of these categories even are. We’ll get onto that later, because it’s funny as fuck.

Let’s take a look at the report in all its glory.

Sampling

Every dataset needs good sampling for good research. This pan-European study used 7,974 participants, which on the face of it sounds pretty good. The researchers identified eight regions to explore and aimed for 1,000 participants from each. The regions were the UK, France, Spain, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Romania and Scandinavia. You might spot that one of these things is not like the others, in that Scandinavia is not a country. But that’s the least of our problems.

In fact, over 37,000 participants were recruited into the study. Over 10,000 weren’t used in the analysis because they didn’t complete the survey; and almost 15,000 weren’t used because their responses were “low quality” (no information available as to how the research team assessed whether a response was low quality or not. Another 4,000 or so were excluded because they’d already hit quota limits – again, not any information as to how they chose which ones to exclude here, I’d assume it’d be the last ones to complete the survey from a specific region, but they don’t say so I could just make up any old shit.

So, the key takeaway is that the analysis was undertaken on about 20% of people who actually participated in the research. This is a bit of a shocker; while drop-outs can be expected, it’s generally not good practice to throw out almost 80% of your dataset.

I have a theory as to why drop-out was so astronomically high, though…

Multiple tests

The survey didn’t just measure these “deviant” behaviour variables (more on these later). It was, by the looks of all the measures they used, a heckin chonker of a survey, which also included the following measures and scales: the technical competency scale; the Emotional Impairment, Social Impairment, and Risky/Impulsive subscales of the Problematic and Risky Internet Use Scale; Adapted Risky Cybersecurity Behaviours Scale; an adapted version of Attitudes Towards Cybersecurity and Cybercrime in Business scale; the Toxic and Benign Disinhibition scales of the Online Disinhibition Scale; a few subscales from the Low Self Control scale; the Minor and Serious subscales from the Deviant Behaviour Variety scale; an adapted scale to measure deviant peer association; parts of the SD4 scale to measure “dark personality traits” of Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, Narcissism and Sadism; and also measures of anxiety, depression, and stress.

That is a lot of questions. A lot of participants would be bound to give up on it. And some are bound to not take a survey seriously if it asks you if you steal cars in one question, then goes on to ask if you’ve ever torrented a movie in the next. Come on. That’s literally this meme.

The bigger problem of measuring so much, as the researchers did here, is that this means they’re conducting a hell of a lot of statistical tests, which raises the probability of something coming up as significant when it isn’t. The further problem is they barely report any results of any of the measures they did. This points to one of two dodgy research practices going on. It either reflects the “file drawer problem”, where research not finding anything does not get published, or “slice and dice”, where they’ll publish findings from the same dataset across multiple studies. Both are forms of publication bias, and both practices are fairly frowned-upon as they’re bad practice and make systematic reviewing of the research difficult.

Let’s look at the bit they actually did publish: the risky and criminal behaviours.

How are the behaviours defined?

The thing is, the definition of the behaviours in the study are pretty bad, too. Many are named in a way which sounds much worse than it is, for example “self-generated sexual images” in fact translates as “sending nudes” (or, as the researchers put it, “make and share images and videos of yourself that were pornographic”). ]

Others are just so broad as to be hilarious. A few favourites:

• Trolling is defined as “start an argument with a stranger online for no reason”.

• Tracking is “track what someone else is doing online without their knowledge”, which covers everything from stalking to looking at your ex’s instagram once in a while.

• Illegal trade of virtual items is buying or trading virtual items, a practice which is literally encouraged by some videogame brands.

• Digital piracy is “copy, upload or stream music, movies or TV that hasn’t been paid for”, which if you’re asking it this way, also includes things like watching youtube or free-with-ads content.

In short, some of the measured behaviours are very badly-defined and it is frankly a miracle that the numbers of young people doing these things are so low.

However, after doing yet more statistical tests, the researchers conclude that some of these behaviours cluster together. Do they?

Clusters of behaviours

The researchers conclude that, thanks to their research, “A significant shift from a siloed, categorical approach is needed in terms of how cybercrimes are conceptualised, investigated, and legislated.” Can they really support clusters of behaviour with their data? As far as I can tell, no.

There are many statistical methods for inferring clusters within data, ranging from techniques which look at “distance” between variables, to multidimensional scaling, to artificial neural networks. It’s a whole branch of mathematics.

The researchers used none of this veritable smorgasbord of algorithms, and instead ran a bunch of correlations as far as I can tell from their reporting. Then they somehow arrived on a cluster of the ones which had the biggest correlations with each other, for example, online bad’uns who are racist are also probably engaged in money laundering and revenge porn. It’s hard to tell exactly what they were doing, because the reporting of the method is very vague, but if they were using any of the multitude of established cluster analysis methodologies, they’d have probably mentioned that. When someone uses principal component analysis, they tell you about it because it’s a massive faff.

Conclusions from their conclusions

In short, what we have is a study with eyebrow-raising sampling methods, running multiple tests on the same dataset (without publishing the results of most of them), with some very weirdly-defined variables, and vaguely-described statistical methods. It’s not replicable. A journal probably wouldn’t print it, and indeed it wasn’t printed in any peer-reviewed journal.

It’s clear that the study authors had an agenda, which is always a bad place to come from when creating research; it generates bad research. Author Mary Aiken outright states the agenda in the Guardian report on the research:

“The online safety bill is potentially groundbreaking and addresses key issues faced by every country. It could act as a catalyst in holding the tech industry to account. The bill sets out a raft of key measures to protect children and young people; however, our findings suggest that there should be more focus on accountability and prevention, particularly in the context of young people’s online offending.”

Guardian, 5th December 2022

This is, essentially, a study which is manufacturing consent for the Online Safety Bill, a disastrously poorly-thought-out bit of legislation. And she’s out there saying “actually, it should probably be made worse because young people are internet criminals”.

This is worrying, to say the least, and yet it is entirely par for the course. The bill is a hot mess, and it needs some form of justification. This study, I don’t doubt, will be trumpeted around for some time, arguing that the delinquent kiddos need protection from themselves.

A huge thank you to some of the lovely people on Mastodon for talking this through with me (and sharing mutual snark). I probably wouldn’t have been inspired to write this many words about this without those chats. I’ve thanked a few who specifically helped in this post and there’s more quality snark and insights in the replies here.

_

Enjoyed what you read? Consider becoming a Patron or leave a tip